We sat cross-legged on the carpet in the living room at the gathering after his presentation, just me and Alfredo Jaar, the other guests chattering on the surrounding sofas and chairs, invisible and inaudible to my eyes and ears,. “So what do they teach at the Kennedy School?” he probed, after I invited him to give a lecture on leadership. I could see that he was wondering what an artist specialized in public art installations could possibly contribute. “I’ve spoken to artists, photographers, intellectuals, poets, authors – no – never to students of leadership”. Shame, I thought, we have so much to learn from Alfredo Jaar.

It was a hunch – “Parlez-vous francais?” I asked en passant and he responded in the most articulate, poetic French. I knew that he was born in Chile and now made his home in New York. Now he shared that he had lived as a youngster for ten years in Martinique. Back and forth we went between my two native tongues. My mind was still abuzz about It is Difficult, the lecture he had just given, talking us through his work, his approach and methodology, the projects he undertakes and in particular his intervention installation in Skoghalls, Sweden. I thought of how many community and arts leaders have struggled for decades to build a museum or an art gallery in their town or city. How they gathered friends and colleagues and established a committee, raised money, secured a site, got land-use approval, hit an economic downturn, started over, replaced dispirited founders, witnessed the site be repurposed, rallied a new team, and on and on. In came Alfredo Jarr, from Chile through New York to Skoghalls and with one public art intervention, in one day, managed to make a cultural space a priority for this Swedish community.

Trained as an architect, Alfredo now devotes one third of his time to museum works, one third to the creation of public art and one third to teaching by directing workshops and seminars around the world. But my focus was on the methodology he adopts when he goes into a community to create a public work. At the beginning of his career, he would engage in what he termed guerrilla operations. Today, he receives numerous invitations per year by communities and institutions and accepts just one or two. He has the luxury now of setting the conditions for the “commission” which is effectively a carte blanche to create his art, referring to what geographer David Harvey calls “spaces of hope”.

For an artist, his process or methodology is unusual by most standards. First, he chooses his “partners” by carefully assessing who is doing the inviting. To him, the patron or client-artist relationship is a partnership. Is there chemistry and can he trust the people and the institution to be with him for the long run? This, the second point, is essential because he will insist on having the leeway to make as many trips to the community as necessary before producing a work. At times, he is joined by one or more of his assistants, and some research is conducted via the internet. But “nothing beats being there” to interview the people, to observe, to survey both geographically and structurally the meaning or the essence of the city. “Context is everything” he exhorts “and I cannot act without understanding the context or where I am”. It may take up to nine visits for him to reach what he calls a “critical mass” of information so that he can distill things down to one core issue, to articulate a single idea.

For this third step, Jaar stresses the importance of the singularity and simplicity of the idea that will ultimately be embodied in his final work. His methodology or process is about editing, the power lying not in trying to a great many things, but in the single concept. And while he is aware that there may be more than one issue, he waits until he has enough data to intuit which issues he is not in a position to tackle. He claims his research is finished when he has become a part of the community, when he has become invisible. Thinking like an architect, he identifies success from the outset and works towards that. And he reflects further on the advantages of being an outsider: “The last one to realize it is in the water is the fish. And you only realize that when you are taken out.” He can say things through his art that no one else can.

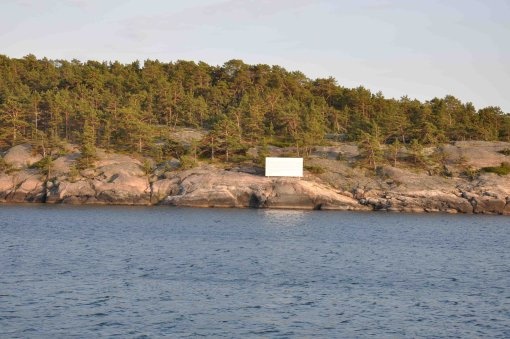

As he did in Skoghalls. This middle class, “company town” boasts a population of some twelve thousand, and the entire economy revolves around Stora-Enso, a manufacturing plant that rolls out reams of the treated paper used for milk and juice cartons. During his research, Jarr became appalled at what became glaringly absent to him – any cultural life or public space for art. In fact, he would hear later from a survey conducted by one of the local students that the reason no one ever thought in fifty years to have a museum was that the community didn’t need one. He boldly stated his observations to the Stora-Enso board after rejecting the commission from the town: It is time for Skoghall to present to Sweden and to the world a new image, a contemporary image of progress and culture, beyond being a dormitory for the Paper Mill workers. An image of creativity and actuality. An image of a dynamic and progressive place where culture is created, not only consumed. A living culture is one that creates.

He then formulated the following proposal for a temporary contemporary art museum:

The Skoghall Konsthall

I propose to design and build a new, contemporary structure to house the new Skoghall Konsthall. This structure will be built completely in paper produced by the Paper Mill, in close collaboration with local architects and builders.

The design will reflect the best of contemporary Swedish architecture in its minimal elegance and respect for the environment. It will also reflect the generous commitment of the main local industry in the creation of a forward looking structure and institution that will project Skoghall into the future.

The opening exhibition

The opening exhibition will feature the first exhibition ever held in Skoghall of young emerging Swedish artists from Stockholm, Malmo and Gotenburg. The Konsthall will be officially inaugurated by the Mayor of the City, in the presence of the entire local community.

The Closing Ceremony

Exactly 24 hours after its opening, the Skoghall Konsthall will disappear, engulfed in flames. The burning of the structure will be pre-planned and will satisfy the most demanding security requirements.

Epilogue

By its paper nature and design, the Skoghall Konsthall will probably be one of the most advanced contemporary paper structures ever created for contemporary art. But it will also be one of the shortest-lived structures ever created for contemporary art.

I am hoping that this combination of creativity and ephemeral existence will perhaps help define the importance of contemporary art in our lives.

And it is my hope that the extremely short life of the Skoghall Konsthall will make visible the void in which we would live if there was no art. And this realization will perhaps lead the city of Skoghall into the creation of a much-needed permanent space for contemporary creation and projection.

Alfredo Jaar, Notes on The Skoghall Konsthall, 1999

They built the paper museum, the majority of citizens attended, the paper mill orchestra played and the Mayor made a speech. The newly minted “museum goers” proudly toured the exhibits, rubbing shoulders with their friends and family, enjoying this unique opportunity to enjoy art together in their new arts and culture space. Twenty four hours later, everyone came back, the site was cordoned off, the Swedish flag was ceremoniously removed from its pole and firemen in asbestos suits entered the structure and took a blow torch to the timbers. The town watched in horror, dismay, disgust, sadness, remorse, resentment and anger as their new Kontshall was engulfed in flames. Within a year plans were afoot for a space for culture and seven years later, Jaar was invited to design a museum.