In 2012, while pursuing a Masters in Theological Studies at the Harvard Divinity School, I won the draw for one of the slots in the Negotiation J-Course offered at the Harvard Law School. I reminisced to my law school studies at the University of Alberta in the 1980’s and back then, “Negotiation” as a course was not a thing. This would be a fun choice for an elective. My background is in the arts and so, for the class paper, I opted to provide ideas for arts and experience based methods that might help convey the themes being taught. This segment addressed a simple and effective listening technique I had picked up auditing the Presencing Course taught by Professor Otto Scharmer at MIT.

It was made clear throughout the course that “active listening” is a high priority skill in negotiation as it is entangled in so many of the key concepts. First, it is essential for good communication – for developing our capacities of inquiry, acknowledgement and paraphrasing. Second, it is only through active listening that we can hope to develop empathy for the other. Finally, it is tied to relationship building and is a skill that is invaluable in life, one that can so easily improve all of our relationships and help us be more present, more aware.

Granted, the practice of communication techniques like inquiry, acknowledgement and paraphrasing hone our listening skills. But given how important this skill is for negotiation, there would be no downside to incorporating a more rigorous training practice to the curriculum.

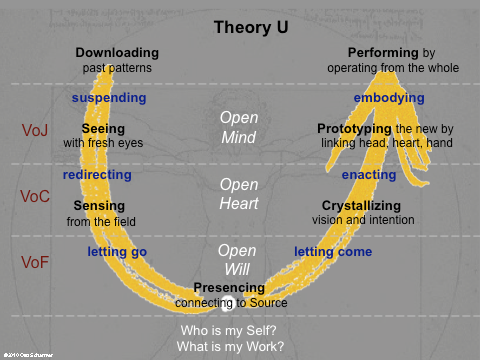

The diagram below represents Otto Scharmer’s Theory U, the subject of The Essentials of Theory U and the “Presencing” course he taught at MIT’s Sloan School of Management. I was struck by his reframing of Buddhist principles of mindfulness into what he calls a deeper learning from the emerging future or presencing. Presencing blends the two words “presence”, the now, and “sensing”, the capacity to detect what is to come, to sense an emerging future possibility and then to act from that state of awareness in the now (“sensing and actualizing emerging futures”).

The first series of listening exercises revolved around what he defined as four levels of listening. Our homework was to engage in a conversation with a complete stranger – someone on the train or bus, your hair stylist, perhaps a person on a park bench. Open a conversation and then ask questions about them and their life and simply listen. Listen and observe the different levels and try to attain the fourth.

- Listening 1: to attend to what you already know – or “downloading” – hearing what the other is saying without paying much attention.

- Listening 2: to recognize some new external facts (factual);

- Listening 3: to see a situation through the eyes of another (empathic).

- Listening 4: to sense the highest future potential of another person or a situation (generative).

As I began to take note of the different levels of my listening, I realized how difficult it is to practice Level 4 Listening, to remain laser-focused on what the person is saying and doing, and not on my thoughts. I realized how often I was “downloading” but as I moved up the scale, it was helping me stay in the moment. When I fully concentrated on the person I was speaking with, when I listened to what they were saying, when I paid attention to their words, to their voice as a window to their feelings, their fears, their anxieties, I could far more easily access my own empathy and compassion. When we were both fully engaged, new possibilities emerged, transformation was taking place.

In addition, as I sat and listened, it quieted the ongoing chatter in my head, stopping me from a tendency to butt in, give an opinion, prefigure how I might respond, cease listening to formulate an answer, or simply wander off to another world. It is a scientific fact that we can have only ONE consciousness “event” at a time. As I sat and listened I noted that the person I was with sensed being valued, a hint of surprise that they were actually being heard. People really liked being around me when I practiced Level 4 Listening. I also rarely said things that I regretted later and I felt good about the conversations. How I listen deeply impacts the current and ensuing conversations. Scharmer describes the phenomenon as follows:

Each type of listening results in a different outcome and conversational pathway. In short: depending on the state of awareness that I operate from as a listener, the conversation will take a different course. “I attend this way, therefore it emerges that way.” The stages and states of conversation change from “talking nice” and conforming (Field 1: downloading), to “talking tough” and confronting (Field 2: debate), to reflective inquiry—i.e., seeing your self as part of the larger whole (Field 3: dialogue), to collective creativity and flow (Field 4: presencing). Through conversation, we as human beings create our shared reality. The different field states of conversation determine the possible pathways of thinking, collaborating, and innovating in teams and organizations. The quality of collaboration depends on the interior condition from which we operate.

This model of listening could be introduced as a supplement to the “active listening” skills and we could practice it in pairs for fifteen minutes and debrief. Then, an exercise might be to journal daily for one week on listening and note how many times during the day we practiced Level 4 Listening, how much of our day was spent on the other levels. We could also debrief on how well we listened following our negotiation exercises. Just like any other muscle, listening as a skill can be exercised and strengthened.